While the sounds of machine guns firing blanks during the Fort Riley Fall Apple Day Festival could be heard in the distance, Dr. Claude Harwood, 93, was visiting Fort Riley and the 1st Infantry Division and recalling his time with the “Big Red One.”

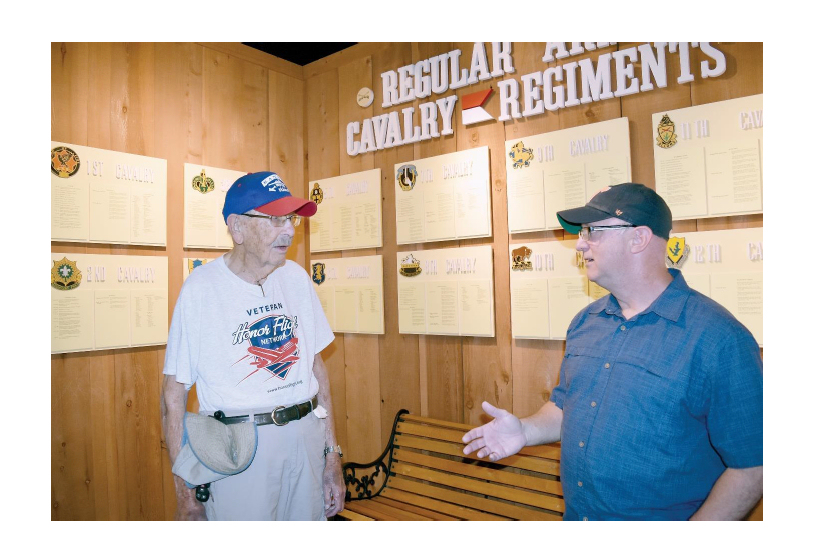

“Doc” Harwood walked into the Cavalry Museum and the tat-tat-tat receded into the hush of history on display. He began to talk about his service in Germany during WWII and explained how his meeting with his first company commander there didn’t go well.

“Our command post was in kind of a — well it wasn’t really a basement, it was the lower floor of a barracks building, a German barracks building,” Harwood said. “When I came in there, this is kind of gross, they had a number nine can for urination and I kicked that can over and poor Lt. Magnaberg he hit the ceiling. After he settled down, he said, ‘Well, we’re going to put you out in the perimeter for night watch.'”

Harwood described the position as a fairly deep foxhole about 50 feet from the headquarters building and between 200 to 300 yards from the German line. They couldn’t get to it safely in the daylight as any movement drew fire from German machine guns. So they crept out to the position after dark, relieved the previous man and Harwood spent the next 24 hours, his first full day in the combat theater, in that hole.

“I’d been there about an hour or two and there was machine gun tracer bullets fired at a 45-degree angle,” Harwood said. “I guess that was to get you to poke your head up to kind of look around and see what was going on and then there was a strafing — no tracers at all — just machine gun bullets about 18 inches above that foxhole. Fortunately, I stayed down in there. I’d heard about that … you want to keep as low as you can.”

Doc then divulged the tensest few minutes of his first night watch. “Then during the night, I heard some activity outside of my foxhole,” Harwood said. “I thought maybe that was Germans creeping up there. I had a Browning automatic rifle and I cocked that thing just ready to fire it and this great big ol’ Belgian rabbit hopped out. Boy, I was sure glad to see him. That was my war story for my first night on the front line.”

Not every night of his two years and four months at war was “hare” raising. Harwood said some nights were spent with dirt and shrapnel raining down and some were spent snug in an improvised dugout with a few candles for light and a little heat, a blanket and a wool coat in the deepest parts of winter. Harwood served in what would prove later to be the longest series of battles of the war and it would ultimately claim enough German and American casualties to populate Manhattan, Kansas, or about 61,000 in all. The battle was for control of the roads through the Hurtgen Forest and was a major objective before crossing the Rhine River. The campaign holds the record for the longest land engagement in U.S. Army history.

Harwood arrived just as the village of Aachen fell and, according to the Cantigny Military History Series on the “Blue Spaders” of the 26th Infantry Regiment, the objective of the rest of the campaign through the Hurtgen Forest was a push to control the road and cut off the Germans’ ability to resupply their troops.

While Harwood’s unit, Company I, 3rd Battalion, 26th Infantry Regiment, 1st Inf. Div., made its way across the forest, another unit battled for control of Hill 400. From the top of that 400-meter hill, the German soldiers had a view of the entire forest — including the area Harwood and his battle buddies occupied as they went along. The New York Times reported in September 1944 that the hill finally fell to Allied troops. But Harwood said he didn’t know about Hill 400. His unit didn’t encounter much small-arms, close-in combat. They encountered mortars and machine guns as they moved out to occupy the area captured by the troops ahead of them.

“I was just there and I remember going into it,” Harwood said about the dense forest. “It was just dark; trees everywhere. I guess they had some prepared positions because I don’t remember digging a foxhole or anything in the Huertgen Forest. The main thing I remember about it is the Germans would set their mortar shells — the fuse on them — so when they hit a tree limb or something like that they’d explode and just shower the area with shrapnel. And you could hear that shrapnel coming down.”

Harwood gave credit to his helmet for protection. “I never did get hit by a piece of it,” Harwood said and tapped the side of his head with a finger. “Of course I had a steel helmet. I guess it might have shed them off you know?”

It wasn’t until the push through the forest was completed that Harwood was wounded. “I was wounded just as we came out of the Huertgen Forest,” Harwood said. “As we exited the Huertgen Forest there was a little village. I don’t know, it was probably a quarter — a half mile — I don’t know how far it was from the edge of the forest. We went in there just at dusk. It was the day … it was Thanksgiving Day actually. This building had been pretty badly damaged but the basement was still intact … Even though the top of it was damaged, the basement was pretty much intact. So I had, well all of us did … We kind of set up in the basement and couple of us would be up on the floor above and kind of watch for Germans. The guy that I relieved said he saw some Germans walking down the street but he thought they were on patrol or retreating and no shots were fired or anything. When I came out I didn’t see any Germans at all — they’d probably fled.”

The lack of an enemy wasn’t the only thing Harwood found himself thankful for that day. The president had made a promise and that evening Harwood received the fruit of it. Two years earlier, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt signed the bill officially establishing the fourth Thursday in November as Thanksgiving Day. And this year was special.

“President Roosevelt said every American was going to have turkey on Thanksgiving Day,” Harwood said. “And sure enough, after dark, a jeep rolled up with turkey sandwiches — a piece of turkey between two slices of bread and some half-warm coffee — that was my Thanksgiving dinner, so I appreciated it — I mean it tasted good. I had it over a newspaper so I could collect the crumbs and get every bit of it.”

It was the next day when Harwood would meet the bullet with his name on it.

“The next morning after breakfast — I think I had a K-ration or a C-ration for breakfast and as I was finishing that this one plane came over. There were two tanks that came up during the night and they were on either side of that building. I doubt if it was a German plane. I never did see it. It was only one plane and the Germans usually were just one plane. The Americans usually would come over in swarms, they had a lot of planes. But anyway, this plane strafed those two tanks and I think probably it was because they had failed to put out the proper identification panels and he was just warning us we’d better be careful. But one of those bullets came through the roof of that building and went right through the rim of my helmet and just peppered my face with little fragments of helmet … the bullet went right through the lobe of my ear and put a pretty good gash in it.”

Harwood presented himself to the medical team at the battalion aid station and they sent him to another facility to have the fragments removed.

“I was walking wounded I wasn’t hurt very bad,” Harwood said. “They loaded several of us in a jeep and took us to where we could get into an ambulance and took us to Liege, Belgium.”

Harwood discovered that the hospital there was run by a medical team from the University of Kansas.

“The triage nurse said, ‘This kid is from Kansas,’ and they just gave me the royal treatment,” Harwood said. “I spent a couple of days in that hospital and at night they had the windows all covered with blankets and stuff and you could hear the buzz bombs go over. You knew they were headed for England and they had a peculiar sound that you just couldn’t hear anywhere else … After about two days they loaded us on a hospital train and took us to … a suburb of Paris.”

The stay in that hospital was short and Harwood found himself returned to duty when the German offensive picked up. He’d received a Purple Heart he said he didn’t feel he warranted and a respite he said he was grateful for. He also knew what he wanted to do after the Army, not only because he’d always dreamed of medicine, but because of the treatment he received when he got to the hospital in Belgium.

“I felt like I was home because I thought if I went into medicine, that’s where I would go … the University of Kansas,” Harwood said. “In high school I’d thought about being a doctor. I knew the road was pretty hard, I didn’t know whether I could afford it … but that’s what I wanted to do. After I got out, I got the G.I. Bill and I got my undergraduate education at the University of Kansas and then I went into the University of Kansas Medical Center. So I was able to get through all of that without any debt which was unusual.”

Through help from his parents and his wife, Marilyn, whom he met in college, he transitioned from the rank of technician third grade to doctor. The rank of T-3 is about the equivalent of a sergeant or staff sergeant in today’s Army. But the Army wasn’t quite through — at least not through trying. Harwood said a recruiter tried to entice him back into the Army as a captain when he was close to graduation. He said at that time his duty was to his parents and in-laws as they were aging.

“When I was in the Army I thought, ‘Boy if I ever get back to Kansas I’m going to pretty much stay there,” Harwood said.

He returned to Larned, Kansas, after college and was true to his word. But he did have some advice for Soldiers transitioning out of the Army today.

” …take full advantage of the G.I. Bill because that’s a big thing,” Harwood said. “Like I say, it was something that I benefited from at that time. That was my only VA thing at that time that I did.”

—

Story by Collen McGee / Fort Riley Public Affairs

Copyright © Rocking M Media, 2017. All Rights Reserved. No part of this story or website may be reproduced without Rocking M Media’s express consent.