More than 7% of Kansas foster children went missing during an 30-month period, according to a new federal watchdog’s report that places the state’s rate of runaways among the highest in the nation.

The state was able to locate children after they had been missing for 27 days on average, which was quicker than most states, according to the report by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Office of Inspector General.

The OIG looked at reports of missing children between July 1, 2018, and Dec. 31, 2020, in an attempt to summarize data, examine polices to report and locate missing children, and report on challenges identified by state agencies.

“Children who go missing from foster care are vulnerable to crime and exploitation, which may result in physical harm and even death,” the OIG report said.

In Kansas, where 72 foster kids are missing currently, the peril is evident in the recent death of a transgender 15-year-old. Ace Scott’s body was found in an empty lot in Kansas City, Kansas, days after running away from a state contractor’s office, the Kansas City Star reported.

However, the Kansas Department for Children and Families, which administers the privatized foster care system in Kansas, as well as the advocacy group Kansas Appleseed, questioned the methods and data used by the OIG for its report.

DCF spokesman Mike Deines said the agency was trying to better understand why the OIG used a time period of 2.5 years. The state tends to look at the number of missing foster children at points in time, he said. Daily reports over the past four months show 60-75 foster children are missing at any time, which is about 1% of the number of children in foster care.

Deines said the agency has made significant investments in efforts to locate missing foster kids since the current administration took office in January 2019. That includes expansion of a special response team with 12 members across the state whose sole responsibility is to locate and recover missing foster kids.

“They make contact with family, friends, law enforcement and other community members to better understand where the youth may be and also identify the underlying reasons for the run behavior,” Deines said. “DCF believes that if we can address the ‘why’ these youth run, then we can make better placement decisions and connect them with services in order to prevent further run episodes.”

The average number of foster kids who are missing every day has declined from 90 three years ago to 65, Deines said.

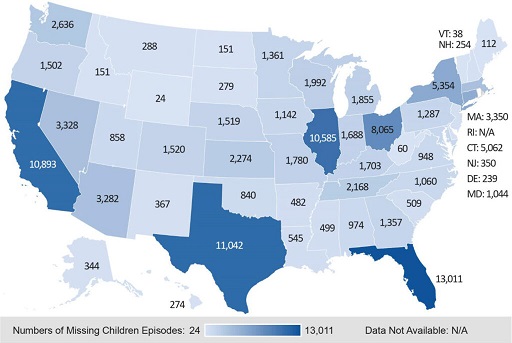

The OIG said there were 2,274 instances of a missing foster child in Kansas during the 30-month window it examined. The numbers were lower in neighboring states, including those with larger populations. Kansas was one of six states where more than 7% of foster kids went missing.

Other states reported as few as 24 missing children, although reporting standards varied from state to state. Some states, the OIG said, only reported children who had been missing for at least 24 hours.

The OIG defined missing children as those who are not in the physical custody of the agency, individual or institution with whom a child as been placed. The actual whereabouts of the child may be known or unknown.

Most states, including Kansas, reported the average number of days for a child to be missing between 7 and 46, although nine states had an average of 50 or more days.

The risk of running increases with age: 65% of missing children were 15-17 years old, the OIG said.

The challenges most frequently identified by states involve the number of children who repeatedly go missing, cooperating from families and friends of missing children, obtaining assistance from law enforcement, and finding a placement to prevent a child from running away.

Quinn Ried, a policy research analyst for Kansas Appleseed, said some of the data OIG relied on for its report are inconsistent with data on the DCF website. Kansas Appleseed is monitoring numbers as part of a federal lawsuit settlement in which the state agreed to improve instability within the foster care system.

Ried said the actual percentage of missing children in Kansas could be anywhere between 6.5% and 7.5% based on his estimates.

“While Kansas has one of the highest percentages of missing children, according to the OIG report, it is below average with regards to average days missing. … This leads me to believe the threshold for reporting a child as missing is different in different states, and therefore the comparisons are maybe less useful,” Ried said.

_ _ _

Story by Sherman Smith / Kansas Reflector