When Kayla Johnson was a young girl, she was fascinated by science. Her interest quickly evolved into a curiosity about medicine, and by the time she started undergraduate studies at Fort Hays State University, she knew she wanted to be a doctor. Shadowing a general surgeon in Hoisington, a 15-minute drive from her hometown, stoked her confidence.

As her decision about medical school loomed, Johnson was delighted to discover in 2011 that the University of Kansas School of Medicine was opening a new campus in Salina. Growing up just an hour southwest of the area in Odin, a Barton County community with a population that hovers around 100, Johnson had often visited Salina with friends and family. She liked the idea of staying close to her roots.

“I remember texting my family that if this happens, I could be close to home and still be in a small town,” she recalls. “I didn’t apply to any places outside the region. Salina was always my No. 1 pick.”

Johnson was accepted into the KU School of Medicine-Salina, one of eight students in the inaugural class—six of whom were Kansans. The University launched the four-year program to help address the state’s ongoing dire need for more doctors, particularly in rural communities. In 2011, 12 counties in Kansas were without a full-time physician, and 97 of the state’s 105 counties were considered medically underserved.

Fortunately, those numbers are shifting, thanks in part to KU’s outreach efforts. According to the Kansas Department of Health and Education, there are now 79 medically underserved counties in the state (a marked decline from earlier reports). University leaders hope to see that trend continue.

“Access to health care is critical for us all, no matter where we live,” Chancellor Doug Girod says. “This will become even more important as our state’s population continues to age in the coming years, further increasing demand. With many of the counties in our state remaining medically underserved, KU has a distinctive responsibility to help fill that need.”

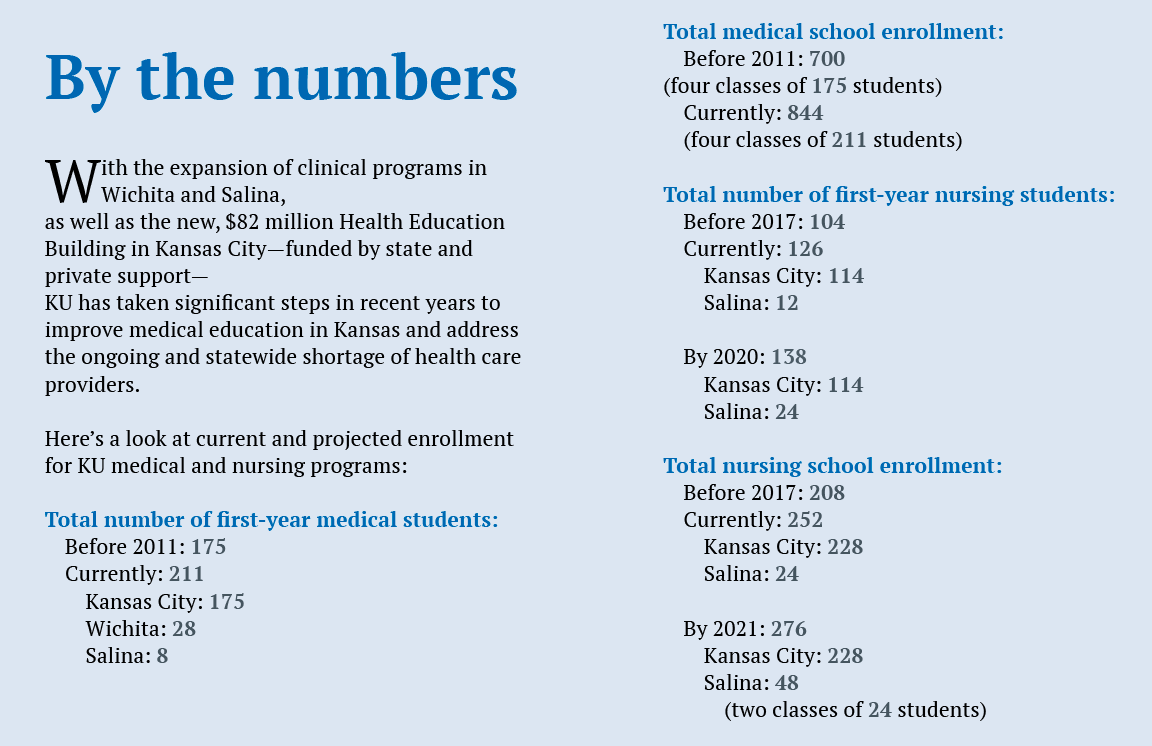

In addition to opening the medical school campus in Salina, the University in 2011 also expanded the School of Medicine-Wichita program from two years to four, allowing KU to accept 211 students each year, up from 175. The goal of both initiatives was clear: generate more physicians for Kansas.

“One of the thoughts is if we can’t recruit them here, let’s grow our own,” says William Cathcart-Rake, m’74, dean of the School of Medicine-Salina. “I think we’re doing that.”

Kayla Johnson, m’15, now a pediatrician in Salina, has done just that.

Cathcart-Rake vividly recalls the day he learned Salina was the anticipated site for the School of Medicine’s new campus. The medical oncologist, who established his practice in Salina in 1979, had attended a Saline County Medical Society event, hoping to hear about changes to the University’s medical school curriculum. The topic greatly interested Cathcart-Rake, whose daughter, Elizabeth, m’13, had recently enrolled at the medical school’s main campus in Kansas City. But the group’s discussion about KU launching a four-year medical program in his hometown really caught Cathcart-Rake’s attention.

Cathcart-Rake’s uncertainty was short-lived. In 2009, at the urging of University officials who wanted a Salina-based, “boots on the ground” physician to lead the effort, he agreed to guide the new program as director of medical education and oversee plans to identify a suitable building for the school, raise funds for critical renovations and medical resources, and hire local faculty and staff. With no state funds allotted for the initiative, the Salina campus had to rely heavily on community support.

John Mize, c’72, a Salina native and attorney who for 40 years served as general counsel for the Salina Regional Health Center, has traveled to several hospitals in northwest and north-central Kansas and has witnessed firsthand the need for more physicians in rural communities. “It made a lot of sense,” he says of KU’s expansion into the region. “This was an easy concept to embrace, just from that experience.”

Mize helped coordinate and guide conversations between the University and local leaders, including Mike Terry, president and CEO of Salina Regional Health Center, and Tom Martin, ’73, executive director of the Salina Regional Health Foundation. The health center provided a $1 million gift to fund faculty and operational expenses and also donated the Florence Braddick Building, a former nursing school on the hospital grounds, which became the Salina campus headquarters in 2011. The health foundation granted $225,000, and Earl, m’57, and Kathleen Merkel of Russell gave $75,000 to support the effort, in addition to substantial funds from the Dane G. Hansen Foundation for student scholarships and numerous gifts from Salina area residents.

“Without community support, especially the hospital and the foundation, we would not have been financially solvent to do this,” says Cathcart-Rake, who in 2014 was named dean of the school.

But even with significant improvements to the Braddick Building, it became apparent within a few years that the School of Medicine-Salina was outgrowing its space. In 2016, the Salina Regional Health Foundation purchased a vacant bank building in the heart of downtown and, with KU Endowment, launched the Blueprint for Rural Health capital campaign, which ultimately raised more than $9 million to fund the demolition and remodeling of the two-story structure and provide contemporary furnishings, technology and advanced medical equipment.

The School of Medicine-Salina moved into the new building at 138 N. Santa Fe in June 2018, along with the School of Nursing, which joined the campus in 2017 under the leadership of Lisa Larson, PhD’18, assistant dean of academic affairs.

With more than 40,000 square feet of space, the new Salina Health Education Center is nearly triple the size of the Braddick Building and provides ample room for both schools. The campus features:

- a state-of-the-art simulation lab with six high- and medium-fidelity mannequins

- a generously appointed procedural skills lab four standardized patient exam rooms

- virtual and gross anatomy labs

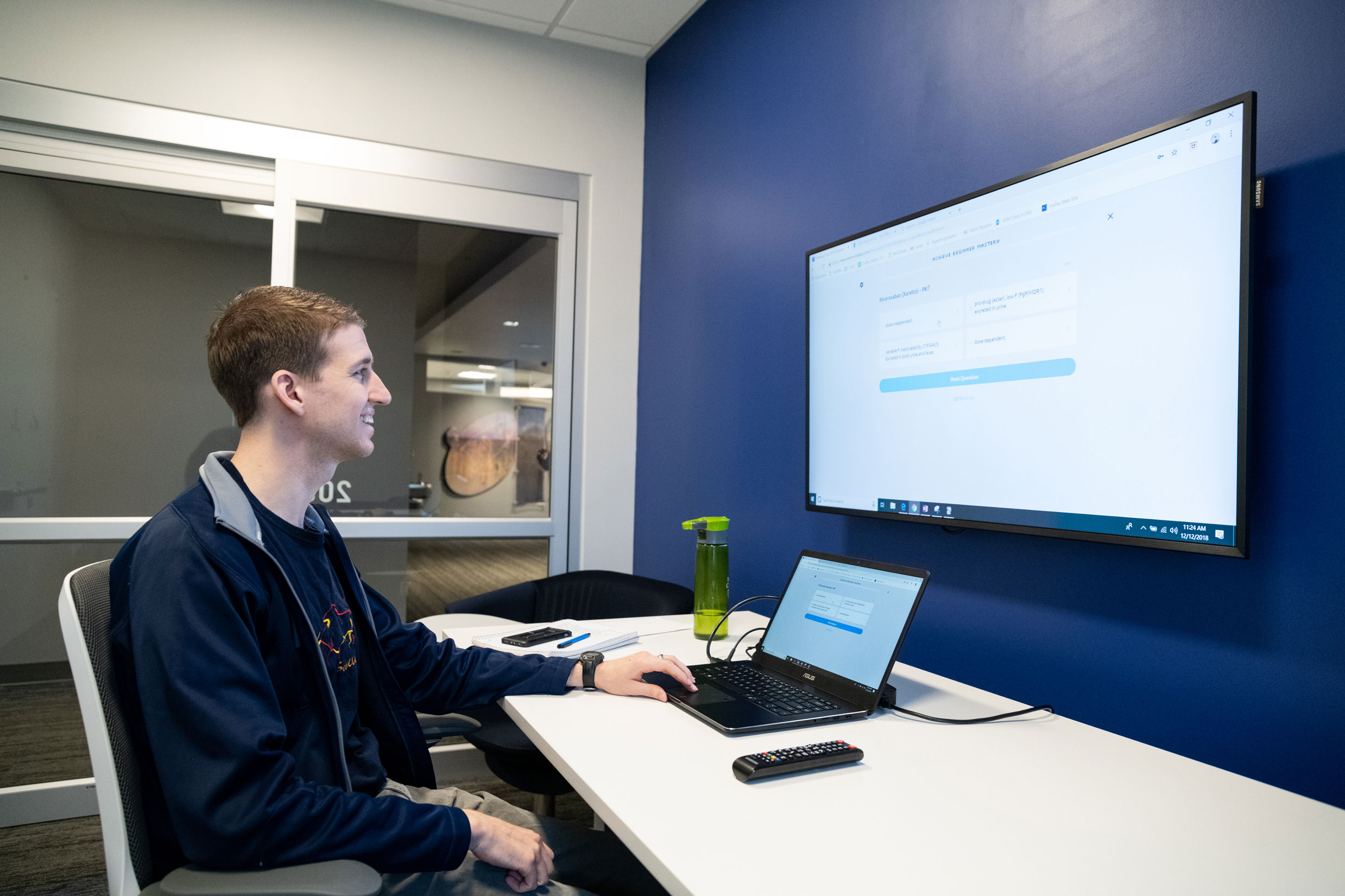

- six classrooms equipped with interactive video links to the main campus in Kansas City

- small-group study rooms and other flexible learning spaces

- recreational facilities and an exercise room

- faculty and administrative offices

- original artwork from six Kansas artists, inspired by rural medicine and the mission of the schools

“With a newly renovated downtown location that serves both medicine and nursing students, we are continuing to provide a high-quality education in a rural setting with the goal of getting as many of these students to return home to their communities as possible,” Girod says.

The new home also makes room for an increase in student enrollment. Though the Salina campus currently caps medical class size at eight, the nursing program aims to increase enrollment from 12 to 24 by 2020.

“The former facilities in Salina were seen as being not as new or shiny or up to date as the campuses in Wichita and Kansas City,” says Robert Simari, m’86, executive vice chancellor of KU Medical Center and executive dean of the School of Medicine. “I think that we have effectively not only removed a potential negative of the older facilities but added a potential positive of the newest facilities in Salina. We expect that interest in going to the Salina campus will continue to increase.”

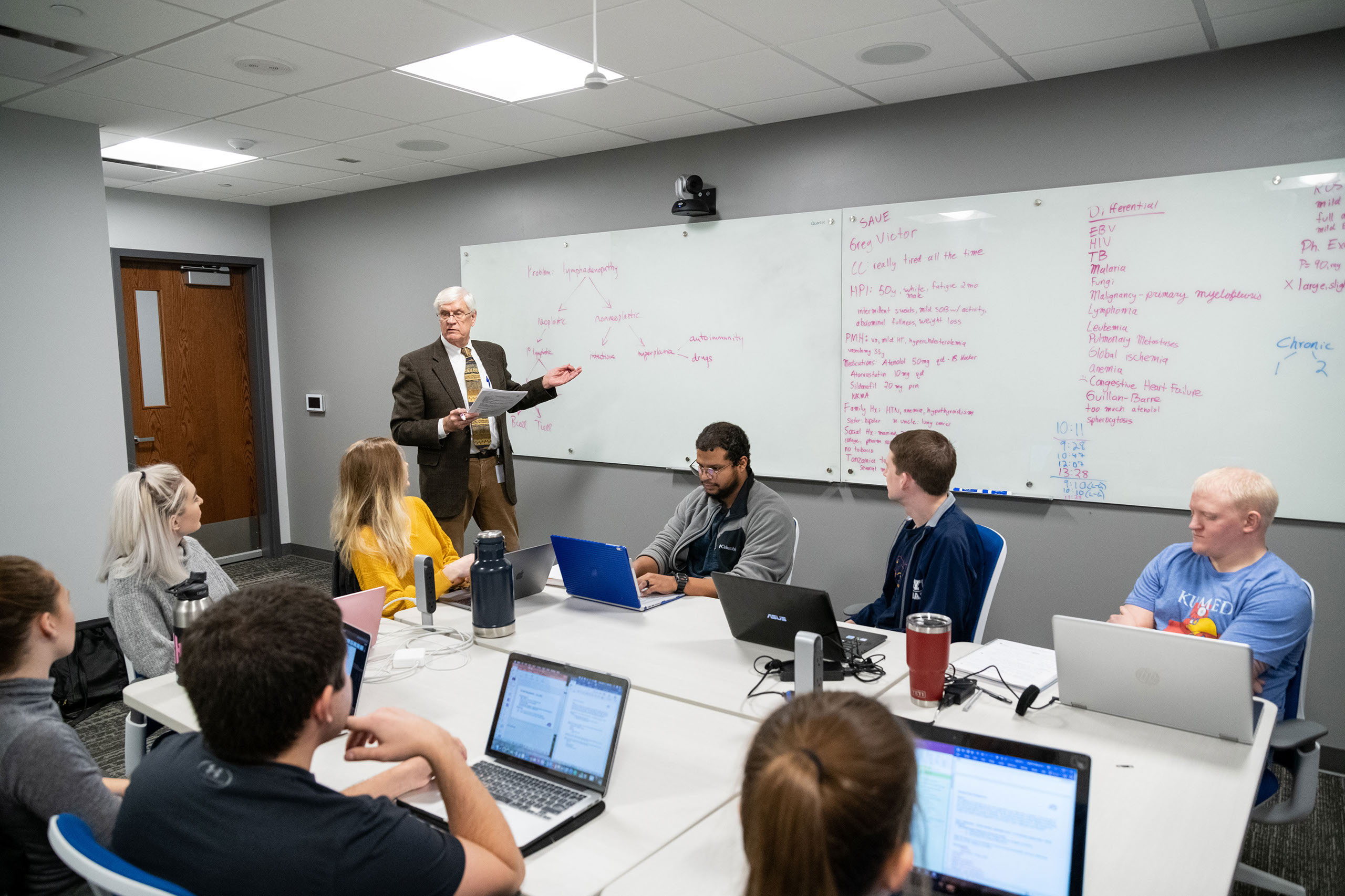

Medical and nursing students in Salina bridge the nearly 200 miles to Kansas City with modern technology, specifically interactive TV, which enables them to participate in lectures and podcasts with their Kansas City peers. In addition, students at all three campuses learn through the same teaching model, the ACE—Active, Competency-based and Excellence-driven—curriculum, implemented in 2017. The new study structure, adopted by several medical and nursing schools throughout the country, means students spend less time in lectures and more time in small, collaborative discussion groups and simulation exercises. The labs and clinical exam rooms at the Salina Health Education Center mirror those at the Health Education Building in Kansas City, which opened in 2017, and feature technology that records student activities for review by instructors.

“There is capability to stream back and forth, so all of the faculty, Kansas City and Salina, can see what’s happening on each campus,” says Sally Maliski, professor and dean of the School of Nursing.

Simulation activities include the use of standardized “patients”—community members who are hired to participate in scripted exams—and training mannequins, which can be manipulated by faculty to mimic a variety of medical conditions and realistic responses. Nursing and medical students often work together during these exercises, emulating real-world health care scenarios.

“We know that we work in teams, but up until recently we trained independently,” Simari says. “By putting nursing students there, it allows for the interprofessional nature of our education.”

The small class sizes—eight for the medical program and currently 12 for nursing—encourage a team approach for students and greater interaction with instructors.

“The one-on-one with faculty is where I’ve benefited the most,” says Elise Foley, c’17, a first-year medical student from Salina. “I can really establish those personal relationships with them.”

Damon Phouvanay, c’17, a first-year nursing student from Garden City, researched both the Salina and Kansas City campuses before making his decision to attend nursing school. “I find I thrive well in a smaller setting,” he says. “It’s cool to be one-on-one with all of your professors. But you’re also remembered in the bigger lectures because they see you on the screen every day.”

Although the Salina campus is notably smaller than its Kansas City and Wichita counterparts, there’s no contrast when it comes to core curriculum and quality of education. “We’re one medical school,” Cathcart-Rake says. “We have one curriculum, we have one set of standards, we have one set of expectations in terms of professional behavior and so on. Despite being one school, we also have something special about our campus. We’re small; we’re rural. On our campus, our students work one-on-one with their attendings. They get a different experience. Now, is it better? I don’t know. We think so.”

“It’s one physician at a time,” he says. “When you’re talking about a small town like Quinter or Phillipsburg, if you can add one physician or replace a physician who’s retiring, it makes all the difference in the world to them.”

Kayla Johnson, who made a commitment to return to Salina during the first year of her pediatrics residency in Wichita, hopes her decision to stay in rural Kansas will improve the community. As one of the newest pediatricians on staff at Salina Regional Health Center, she now has the opportunity to mentor future generations of physicians at the School of Medicine-Salina, including her brother, Kevin Klug, a third-year medical student.

“I’d definitely encourage others to consider practicing in a rural community,” Johnson says. “Not just because there’s a need, but I think this is a really good lifestyle. And you can make a big impact on a community.”

Photos by Steve Puppe / Click to Enlarge